My husband Phil and I have been raising and showing llamas and alpacas for many years. The most frequently asked question we receive when people see these creatures is, “What’s the difference between a llama and an alpaca?”

Even though they share many traits with all other camelids (including the double-padded feet with toenails), it’s easy to tell llamas and alpacas apart on sight. Llamas are taller and weigh more, up to 6 feet tall and 250 to 500 pounds, with long ears, straight back, and high tail set. Alpacas are shorter and smaller, 5 feet tall and 120 to 190 pounds, with wool on legs, neck, and head—either woolly huacaya alpacas or silky, long-haired suri alpacas. Alpacas have shorter, pointed ears, a curved back, and low tail set.

The Colors of Camelids

The alpaca industry in Peru recognizes as many as twenty-two different natural colors, including cream (natural); beige (light to dark, called “fawn” in the alpaca industry); golden, reddish brown; light to dark browns; mahogany (a purple-brown); the grays (silver, regular gray, charcoal, and rose-gray with brown mixed in); and even true black (with no sun fading). Llamas have less variety of colors in their fleeces, probably because breeders (at least in the United States) are more likely to select for fineness rather than hue.

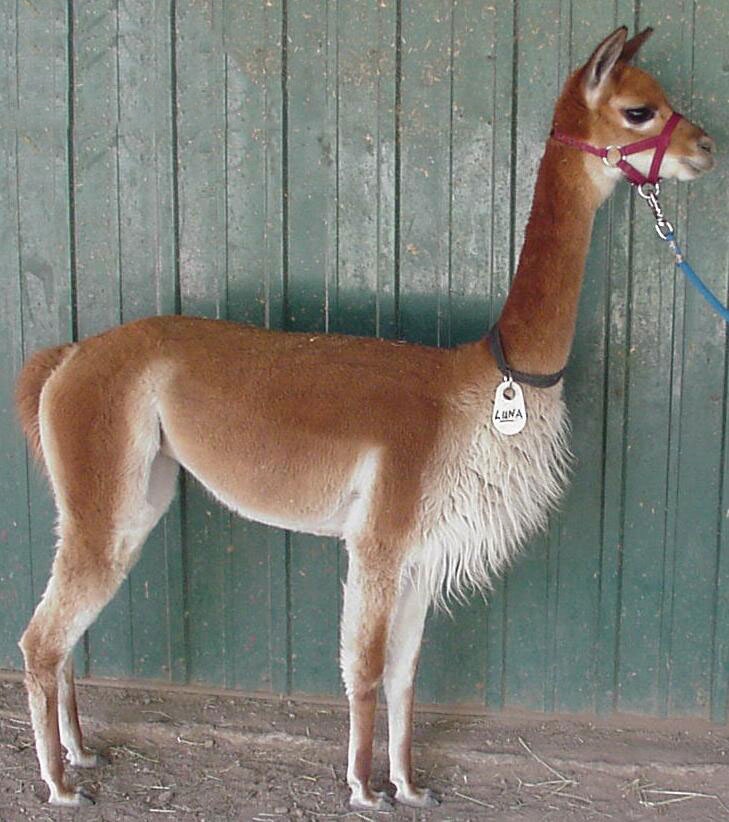

Llamas are larger than alpacas, with long, curved ears (distinct from alpacas, which have more spade-shaped ears). Llama from 711 Ranch. Photo by George Boe

Llamas are larger than alpacas, with long, curved ears (distinct from alpacas, which have more spade-shaped ears). Llama from 711 Ranch. Photo by George Boe

Llamas

Llamas have a double coat with long, coarse guard hairs—not what most spinners are looking for. For my own use, I hand-brush the softer undercoat, which leaves most of the guard hairs behind. If llamas have been shorn, the fiber will be hairy, though some mills do a good job of dehairing the fleece.

Left: Huacaya alpaca. Photo by Fred Gan Right: HFS Jeremiah, an award-winning suri male. Photo by Tim Sheets, Heritage Farm Suri Alpacas

Alpacas

Alpacas have fewer coarse guard hairs than llamas, thanks to many centuries of having been bred for their fiber. We breed our huacaya alpacas for fineness, softness, uniformity, crimp, and density as well as color. A very dense fleece means less dirt and vegetable matter. The first shearing of an alpaca will be the finest, and “baby” alpaca is much sought after (though the name may not refer to the fiber from a baby animal). As the animal ages, its fleece tends to become coarser and develops more guard hairs.

Huacaya alpacas are fluffy, and their fiber has crimp. They must be shorn every year or two to yield about a 3-inch length of fleece. Suris, on the other hand, have long, straight, lustrous fiber, like silk. I hand-clip suris with blunt-end scissors, leaving more fiber along the backline for coverage.

Paco-vicuñas look extremely similar to their wild vicuña cousins, but they retain some alpaca traits (including a calmer demeanor). Photo courtesy of Chris Switzer.

Paco-vicuñas

Paco-vicuñas are domesticated and are also found in the wild. A paco-vicuña is a cross between an alpaca and a vicuña, though in the United States it is not a first-generation cross but the descendant of paco-vicuñas selectively bred to bring forward those traits. In the wild, the colors are the same as those for vicuñas (tan/brown faces, with a rich, tawny brown fleece and light-colored underbelly); with domestication and specific breeding, a variety of colors of fiber appear. We raise paco-vicuñas for finer, softer fleece. The fleeces from our herd range from 13 to 20 microns; by contrast, an average alpaca fleece measures 25 microns. Paco-vicuña is a specialty fiber and a new industry in the United States.

Chris Switzer and her husband, Phil, were the first to raise alpacas in Colorado, and they added paco-vicuñas in 1999. Chris’s book, Spinning Alpaca, Llama, Camel, and Paco-Vicuña, is in its fourth edition.

An earlier version of this article appeared as “A New World Camelid Primer,” Spin Off Winter 2016.